My hole-hearted life: Road tripping and resolution

"The hours on the road were beginning to soften the strings around my heart that have often felt too tight when thinking about my father. The grief associated with losing him is complicated."

I’ve always loved a good road trip. Long drives signal freedom and offer a chance to explore new places, revisit old routes and drive down roads less traveled. And with that intention in place, I decided to drive to my father’s memorial service in St. Louis, rather than fly.

I hoped the 12 to 14 hours on the road from Colorado to Missouri would give me an uninterrupted stretch of time to reflect on the loss of my father, and I decided to split the trip into two days with a small detour to stay the night at a historic hotel in Marion, Kansas, population 2,000. I knew Salina was the halfway point between St. Louis and Denver so I searched “boutique hotels” in the area — something I love to do — and discovered the Elgin Hotel. It was 45 minutes out of my way but the meandering drive through small Kansas towns was just what I needed to begin to unfurl the mixed bag of feelings gathering in my heart like clouds before a summer storm.

I left Interstate 70 and began driving on state highways. My speed fluctuated between 65 and 35 as I entered and left various cities — Lindsborg, McPherson, Goessel. The names were emblazoned in four-foot-high black letters on the water towers that dotted the skyline spread before me, breaking up the flat expanse of farmland and serving as a warning to pump the brakes as I approached another one-block main street.

As I drove, I imagined what it might be like to live in these little towns — another way my curious mind manifests itself, especially when I’m traveling somewhere new. And then I let my thinking take a magical turn as I imagined my late husband Mike riding shotgun. I thought of the dozens of trips we had made together, traveling back and forth from southwest Missouri to the mountains of Colorado where we would eventually live. I remembered the ease of our conversation and how Mike would just listen to me chatter away with a smile on his face, every now and then inserting a chuckle or an observation of his own.

Then, I imagined all the trips Mom and Dad had taken over their 61 years together, and the tears began to flow — urged on by the plaintive country music ballads playing on the only radio station I could get dialed in as I drove down those rural roadways passing more cows than cars.

I thought about how hard the last two years had to have been for Dad after losing Mom so quickly to ALS. The loss of our spouses was something we shared but it wasn’t a subject Dad wanted to talk about. Initially, I thought it was because he was too self-absorbed to care, but over time, I’ve come to understand he didn’t bring up Mike because he didn’t want me to feel sad. And the same held true for him. He rarely talked about missing Mom because I think he just couldn’t bear the pain of it.

On my drive across Kansas and into Missouri, I also reflected on the chaos of the last few years — and the loss. I remembered the rush to move my parents to Denver after Mom was diagnosed with ALS three years ago. In less than a month, we had them packed up, and my brother and I were driving them the opposite direction of where I was traveling now.

The hours on the road were beginning to soften the strings around my heart that have often felt too tight when thinking about my father. The grief associated with losing him is complicated. It is sadness tinged with a little bit of relief if I’m being completely honest.

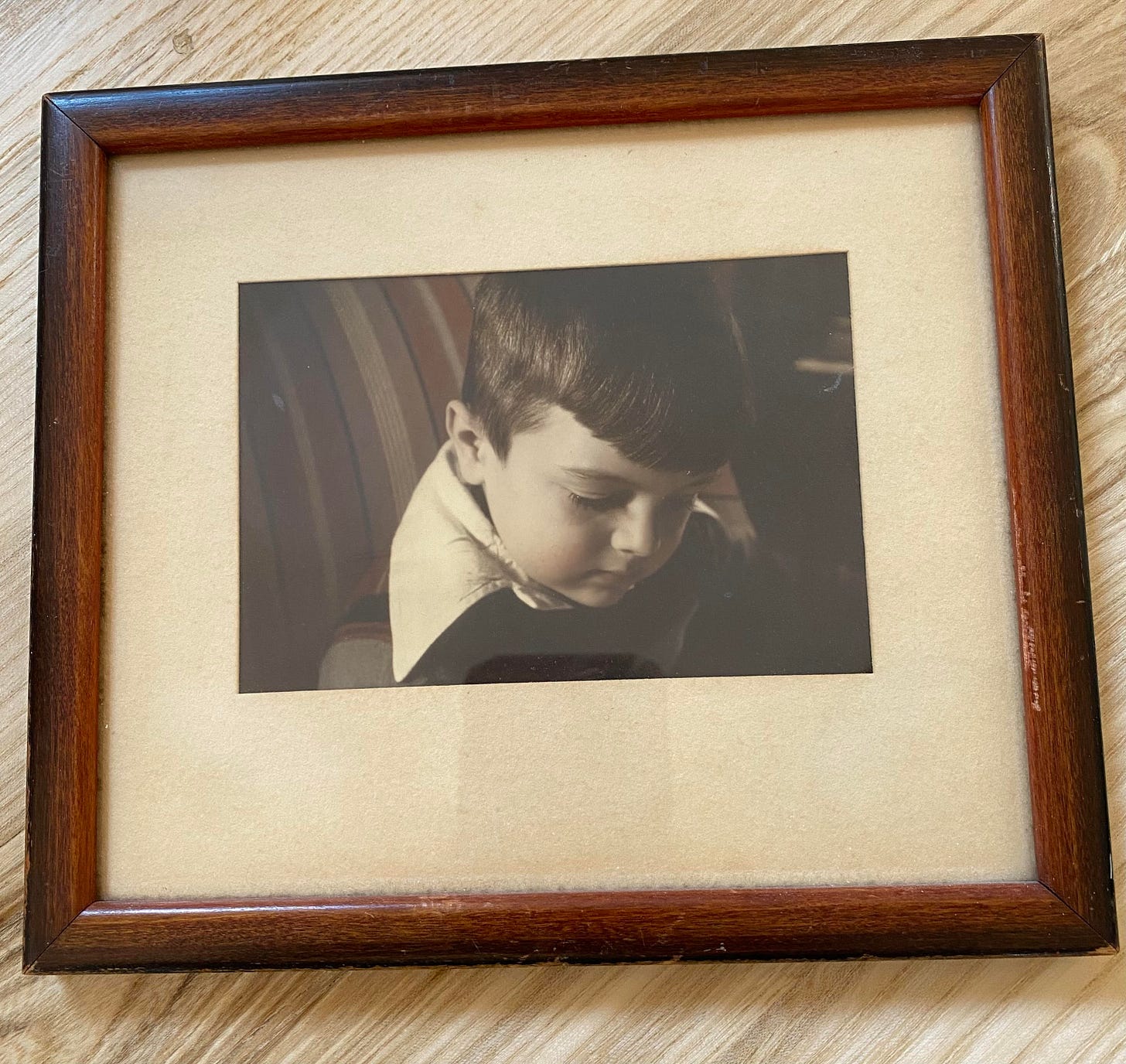

Dad was 89 when he took his last breath, and I was by his side. His entire life centered around my mom, and without her, we struggled to figure out where we stood with each other. Mom was a bright light, a nurturer, a person who loved unconditionally, and in many ways, Dad lived in her shadow. He often joked that living with Mom was like “living with Jesus Christ” and his humor didn’t fall far from the truth. Mom was an extraordinary woman and a rare individual who had the gift for making anyone in her orbit feel seen and heard and loved.

Dad’s kind of love was harder to understand. He was not demonstrative like Mom. He seemed content for her to love his children and grandchildren for the both of them, and while she was living, her love was enough.

I never doubted Mom’s love for me, but with Dad, it was different. He and I clashed, especially when I was a teenager and again when Mom’s disease imprisoned her. His reaction to her condition was mystifying to me, and I thought he was selfish and unfeeling. In those final months of Mom’s life, he directed his anger and frustration at me and that was excruciating to endure in addition to facing my mom’s rapid decline.

When Mom died eight months after her initial diagnosis, we were all in shock, and we fully expected Dad to quickly follow her in death. Instead, Dad lived for another two years. At first, I questioned God’s plan. Why was Dad still here? Why did I lose my precious mother only to be left with my father who was difficult and unloving?

Then, over the past two years, I began finding answers to those questions, unravelling the reasons one conversation at a time. My sister Kristen and I often visited Dad together but there were also times when it was just Dad and me. I’d take him for drives around Denver, and he loved going to visit new coffeeshops with me — one of my favorite pastimes. He began telling me more about his childhood and his relationship with his parents and five siblings, and I began to realize that the way he expressed love was the way he had received love and that explained a lot.

I also came to understand that Dad was acting out of sheer terror when Mom began showing the signs of her disease. The love of his life was dying, and there was nothing he could do about it. He felt helpless and afraid, and at the same time, he was losing his independence. He was living in a senior care community in an unfamiliar city, and he missed St. Louis and the life he had built there. It was the perfect storm of loneliness, sadness and fear, and Dad had never developed the coping skills needed to adjust to his new normal, especially in light of Mom’s rapid deterioration.

Now looking back — with perfect hindsight — I know had Dad died just a month or two after Mom, I would have been left with unresolved feelings of anger and resentment, still questioning his love for me. The two “bonus” years I had with Dad gave us time and space to work out our differences, which benefited us both and allowed Dad’s passing to be peaceful. Near the end, he openly thanked me for caring for him, and he told me many times that he loved me, and that was a gift.

As my road trip wound down, the Gateway Arch that looms over my Dad’s beloved hometown — my hometown — came into view, and I felt an extraordinary feeling of peace spread through my heart like stepping into a warm bath to ease aching muscles. It may have taken two days and 900 miles of driving to get there, but I finally had worked through all that hurt and misunderstanding I’d allowed to accumulate over the years. I was left with a beautiful knowing — Dad loved me the best way he knew how, and I did the same. There was nothing more either of us needed in the end. That quiet love was enough.

Author’s note: While some of my readers know Mike and my parents, many others do not, so I’m providing links to each of their obituaries. I wrote them, which was therapy in itself, and I’m including them to offer insight into who they were and context my future writing.

https://www.steamboatpilot.com/news/obituaries/obituary-michael-eugene-schlichtman/

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/stltoday/name/patricia-neilson-obituary?id=38234159

https://bellefontainecemetery.org/obituaries/charles-hugh-neilson/

I lost my dad at 89, also having a couple more years of him living nearby. He and my mother still appear regularly in my dreams. Yours will too.